Scientists at the Bristol BioDesign Institute have combined synthetic biology with Oracle’s cloud computing software, engineering nanoparticles to create a new vaccine candidate against the mosquito-borne chikungunya virus.

What is chikungunya?

Chikungunya is an arbovirus which, like zika and dengue fever, is transmitted by mosquito bites. Its name derives from the East African Makonde language, meaning “to become contorted” due to the crippling effect that the virus has on the joints. Other symptoms include fever, nausea and fatigue. Chikungunya’s varying levels of severity, from a brief episode to weeks long debilitation, and even death in some cases, means that it is very commonly misdiagnosed. Currently, there are no available treatments or vaccines.

Where is it found?

Since its discovery in 1952, more than 60 countries have identified cases of chikungunya- mostly in Africa, Asia and the Indian subcontinent. “It is usually confined to sub-saharan Africa but because of deforestation and climate change it has started to spread all over the world”, says Prof. Imre Berger, a leading scientist on the vaccine publication. In the last year alone, there have been reports of mosquito-borne viruses including West Nile virus in Germany, dengue and chikungunya in Grenoble and Tarn, France, respectively.

“A major problem with vaccines at the moment is that they need to be refrigerated for storage and for transport, otherwise they become inactivated” Imre explains. This is what is known as a cold chain. Most vaccines, from polio to Hepatitis to the flu must be refrigerated, making the transferral of vaccines to remote or less affluent locations a real challenge.

Bypassing the cold chain problem.

Researchers at the Bristol Biodesign Institute, the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) and Imophoron Ltd have engineered a synthetic protein scaffold that could revolutionise the way that chikungunya vaccines are designed, produced and stored- without refrigeration.

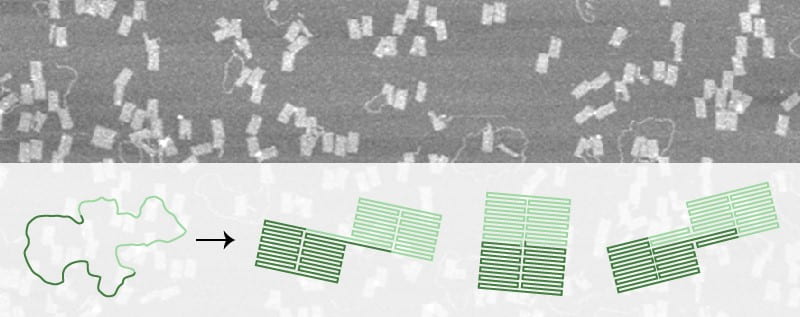

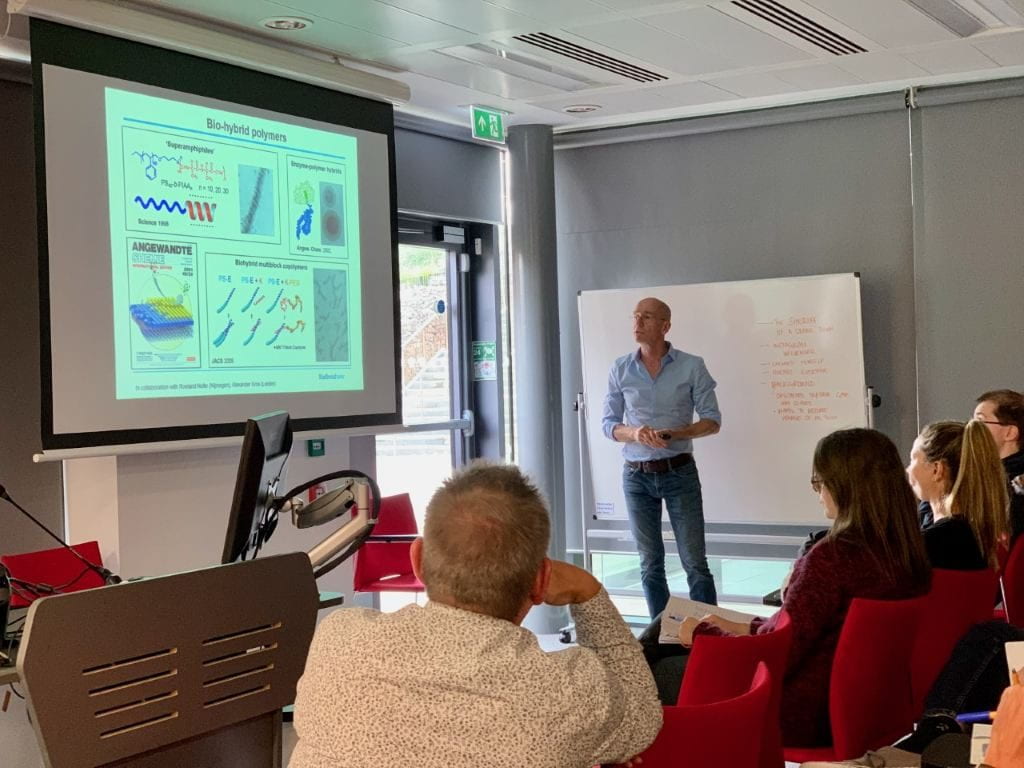

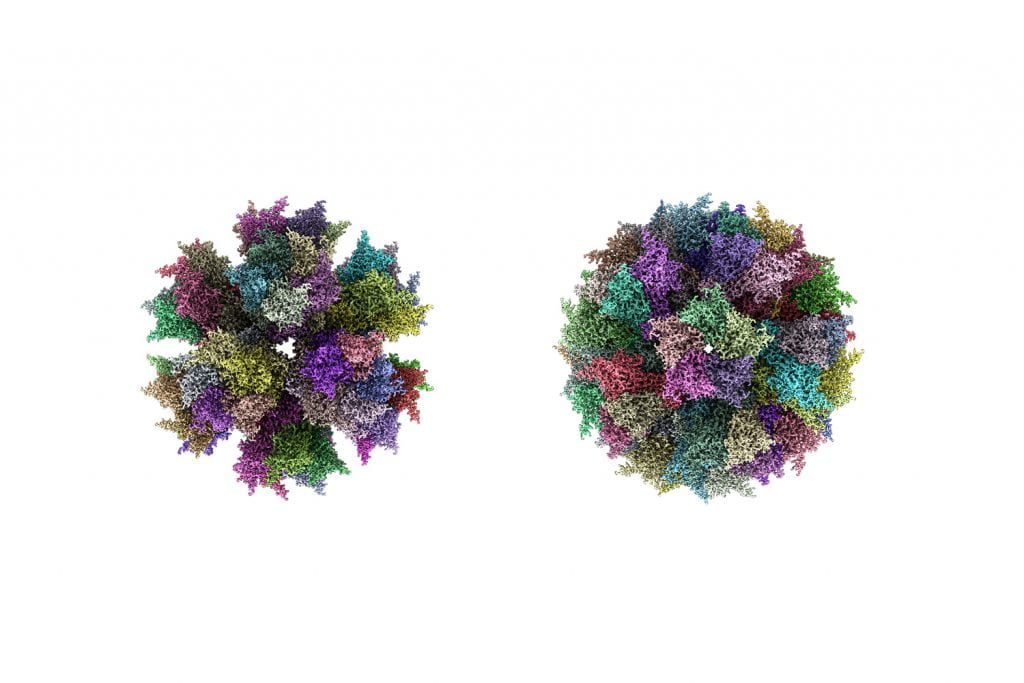

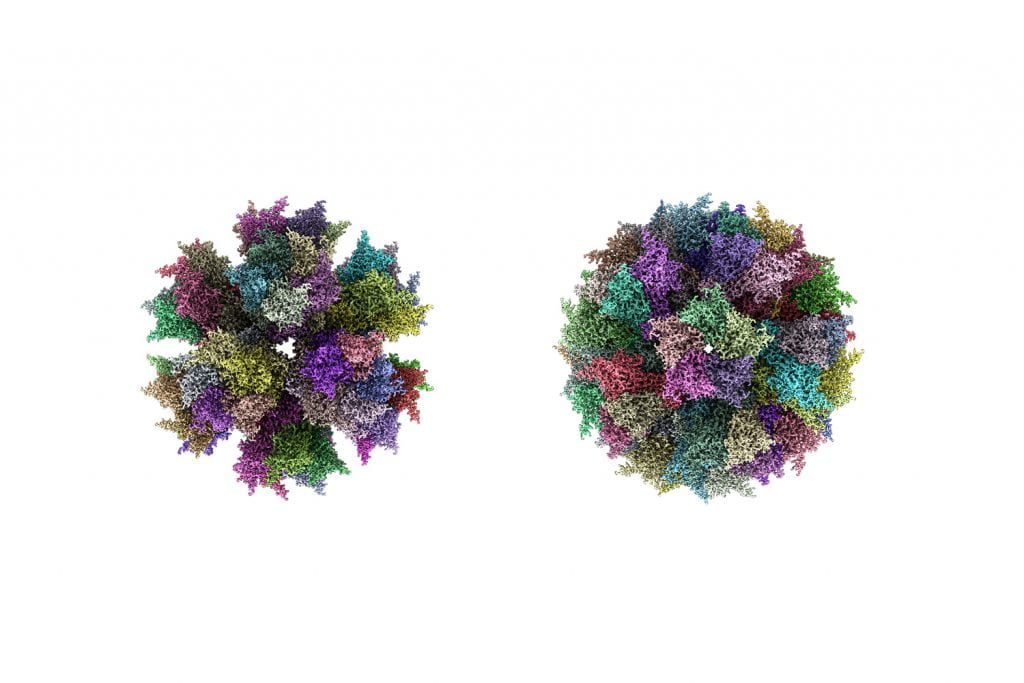

To design this scaffold the collaborators created detailed 3D images of cryogenically frozen nanoparticles viewed through a high-resolution electron microscope, using high-performance cloud computing from Oracle.

How was the scaffold engineered?

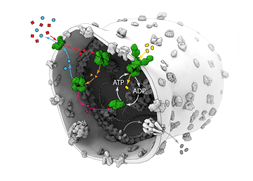

“We have applied synthetic biology to engineer the surface of the ADDomerTM” (which the team have named the manipulated structure) says Imre. “By putting small and harmless pieces of the chikungunya virus on top of the surface of the ADDomer, we can create a particle which looks like chikungunya but it’s not.” This tricks the immune system into developing antibodies against the virus, effectively immunising the body before becoming exposed to the real thing.

The protein-based nanoparticle is a dodecahedron with a quasi-spherical shape capable of spontaneous self-organisation, which makes it ideal as a vaccine platform technology.

To understand the composition of the ADDomer at near-atomic resolution, massive amounts of cryo-electron microscope images of the protein were processed into Oracle’s cloud computing software to produce a single 3D structure.

What is cloud computing?

“Cloud computing fundamentally is the ability to be able to get computing or storage or networking access as a utility”, says Phil Bates, Oracle.

The unique combination of University of Bristol’s state-of-the-art cryo-electron microscopes used in conjunction with cloud computing meant that huge swathes of data could be analysed “in a fraction of the time and at much lower cost than previously thought possible” Dr Christopher Woods explains.

So how is it different to the other vaccine candidates?

“Completely by chance, we discovered that this particle was incredibly stable even after months, without refrigeration” explains Pascal Fender (CNRS). Unlike the previous chikungunya vaccine candidates, the ADDomer is thermostable- meaning that it can be stored for weeks at warm temperatures- thus eliminating the need for a cold chain.

Josh Bufton, from Bristol’s cryo-EM facility, says that “determining the structure of the ADDomer at near atomic resolution by cryo-Electron Microscopy allowed us to both validate the design of the ADDomer as an effective scaffold for vaccine development and gain insights into its exceptional thermostability.”

In short, the accuracy of cryo-electron microscopy, the speed and affordability of cloud computing and the synthetic engineering of the proteins has created a cheap, thermostable chikungunya vaccine candidate that can be produced en masse.

What does this mean?

“What we need to do now for the next step, is to continue the validation in other infectious disease areas and to continue to develop our technology” concludes Frederic Garzoni, Director of Imophoron Ltd. The viability of the ADDomer as a chikungunya vaccine candidate is just the beginning of addressing an entire universe of infectious diseases- both human and veterinary.

Imre adds “in our current paper, we already show more than a dozen other vaccine candidates which we have made. We now have more than 30 altogether and we are very interested to see how powerful our technology really is.”